- 三三云1

- HD中字

蒙骗

- 主演:

- 内详

- 备注:

- HD中字

- 类型:

- 剧情片

- 导演:

- 内详

- 年代:

- 1915

- 地区:

- 美国

- 更新:

- 2024-04-14 11:25

- 简介:

- 伊迪丝·哈代斯将慈善基金用于华尔街投资,希望能买一些新礼服。她失去了所有的钱,并从富有的东方人托里那里借了钱。当她的丈夫给她借的钱时,托里不会收回,在她的肩膀上烙上他的所有权的日本标志。 wwu.edu}Richard Hardy,一个勤奋的股票经纪人,加班加点以应付.....详细

从dropbox里翻出来的大一时候写的文章,凑活着看吧,主要讲了早川雪洲(好莱坞第一位亚裔明星)在这部电影里演的那个角色Hara Arakau,本应该是一个威胁到美国白人中产家庭价值观的反派角色是如何引起观众迷恋的。(主要就是通过对反派实施重要暴力镜头的cut off 还有distancing,让观众得以在一个舒适的区间进行“欣赏”不至于“恐惧”和“反感”,并且通过服化道极尽表现人物身上异域文化的“神秘性”和“欣赏价值”)

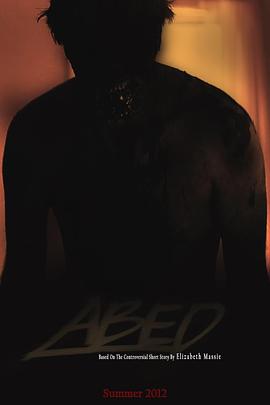

Light shines on a Japanese man in his kimono, gradually illuminating his face, his chest and his hands, which remain crossed in front of him, distancing him a bit from the viewers. He sits at his desk slightly tilted against a completely black backdrop, stares with a serious look for a short while, turns his head and starts working with those strangely shaped but finitely carved objects on the desk. Removing the lid of a brass brazier by one hand, holding a long, stick shaped wooden object in the other, he blows slightly over the brazier, and smoke swirls ominously over his face. He then puts the object inside the brazier, lift it out, and stamps his mark onto the base of an ivory statue. A rapid cut to a close up of his mark: a few strokes that constitute a shape that resembles a temple. He seems satisfied with his work and turns off the lights, leaving us with complete darkness with only a glow coming from the brazier. He stands up a little and the glow lands on half of his face. He puts back the lid of the burner and shadow of cross stripes casts over his face, mystifying his facial expressions.

Accompanied by the beautifully written exotic score played by violin, piano and flute, this scene, the very first scene of the 1915 film The Cheat, introduces us to Hara Arakau, a mysterious, wealthy Japanese art dealer who lives among white middle-class Americans in Long Island. Upon release, The Cheat achieved big box office success. However, instead of being impressed by the leading actress Fannie Ward, the audience became more fascinated with the supporting Japanese actor, Sessue Hayakawa, who played the role of Arakau. This fascination opened a gate for him to become a “full-fledged star” and to achieve superstardom eventually. (Miyao 21) In this essay, I will try to explain this fascination with Arakau through a close analysis of film techniques such as medium shots, extremely extravagant props and costumes in the scene where Arakau assaults Edith Hardy and brutally brands his mark on her shoulder --- the culmination of Arakau as an evil outsider.

The Cheat tells the story of Arakau, the rich Japanese art dealer, offers his money to Edith Hardy, a white middle class woman who has extravagant tastes, after she lost the money from the Red Cross Fund in a failed investment. In exchange, he asks for “the cheat”. Mrs. Hardy tries to return the money after her husband’s success in stock market but gets turned down and violently assaulted by Arakau. During the fight, she shots Arakau. Knowing everything, Mr. Hardy attempts to take the charges to save her name, but Mrs. Hardy confesses the truth during the trial, Arakau gets attacked by the court audience and the couple gets reunited eventually.

First, the film utilizes almost solely medium shots to safely distance the viewers from Arakau when he demonstrates violence and avoids close up shots on his face to relieve them of the burden of getting emotionally attached. The “branding” scene which demonstrates the most physical violence in the entire film consists of mainly three shots: a medium shot of Arakau dragging Mrs. Hardy from the wall and forcing her to lay on his working desk with her faces down, a medium close up shot of Arakau brands his mark onto the the back of her shoulder despite of her fierce struggle, and a medium shot of Arakau pulls her up from the desk, shoves her heavily and she falls down to the floor. Throughout this entire sequence of shots which obviously involves intense physical conflicts and emotions, there is a strong presence of “distance” from the camera to Arakau created by the extensive usage of medium shots and a clear absence of details on the face of Arakau caused by lack of close up shots.

In the medium close up shot of when Arakau conducts the “branding”, which is an extreme form of violence as it exerts great pain, the actual “branding” is cut out of sight. The audience could not see how the scaldingly hot marking tool directly touches the skin of Mrs. Hardy’s shoulder. They could only infer that the “branding” happens through the swirling smoke that rises and the fidgeting arms of Mrs. Hardy. By leaving this extreme violence out of sight, the audience could experience the thrill of “being in danger” without having to bear the pain or feeling unsafe and unsettled. When other forms of slightly lighter violence such as pulling hair, shoving and dragging are displayed in the same scene, the film utilizes a similar strategy --- medium shot. A medium shot automatically creates distance between the object being filmed and the camera. In this case, the distance created would buffer the intensity of the violence for the audience and safely protect them from the “threat” or “danger” that Arakau signifies, leaving them a safe and comfortable space for spectatorship. In other words, when Arakau demonstrates violence on screen, he is a symbol of threat, but this threat is carefully contained in the film through either cutting it completely out of the frame or a medium shot that distance the viewers from it, creating a shield of protection. Therefore, the audience could experience the excitement and thrill one one hand, but also feel safe and comfortable on the other as the “violence” experienced by the female protagonist does not exert on themselves directly. This “thrill but safe” viewing experience provides a foundation for the fascination towards the character Arakau.

It is also worth noting that there is an absence of close up shots featuring the facial expressions of Arakau. Even in the medium-close up shot of the “branding”, he faces slightly downwards towards the desk, with shadows of Mrs. Hardy’s struggling arms keep crossing his face from time to time, making his facial expressions barely discernible to the audience. The audience could only observe his deep frowns, nasolabial folds, indicating he is putting in great effort, but no other information regarding his mental state is being disclosed or revealed. Thus, unable to observe the subtle changes of minute details on Arakau’s face in this critical scene, the audience would fail to connect with the character, to actually understand his feelings and thoughts when he displays these violent behavior, not to mention to empathize or identify with him. This disconnection with the character forces Arakau to stay at the stereotypical image of a Japanese sinister rather than being treated as a unique individual. In other words, since questions like “why does he do this”, “what does he feel when he is doing this” remain unanswered, the viewers could attribute his violent behavior of assaulting Mrs. Hardy to something “evil” or “sinful” innate within him, or worse to some “nature” of his race, culture, or ethnic group. This result might be undesirable in terms of removing racial stereotypes, but it is desirable to the audience as the film provides them with a simple reductive approach to a huge, complicated racial problem. Since Arakau is pictured nothing more than the stereotypical Japanese sinister in the film, the viewers could naturally treat him as one, relieving them of the responsibility to discuss more deeply involved racial issues. Without this agonizing psychology burden of discussing racial stereotypes, the viewers could immerse themselves more in the spectatorship of the character Hara Arakau.

Apart from strategically selecting shot types to create a safe and comfortable space for spectatorship, The Cheat tooks advantage of mise-en-scene elements such as extravagant costumes and props to highlight the mysteriousness and exoticness of Arakau as an “outsider” of white middle-class Americans in New York city. The spectatorship of racial difference itself provides great aesthetic pleasure and joy for the audience which is at the core of the fascination with Hara Arakau.

The “branding” took place inside Arakau’s shoji room rather than his modernized, western style living room that holds the Red Cross Ball, hinting his unassimilable Japanese identity. In the scene where fierce physical conflicts occurred, we could see how Mrs. Hardy is encompassed by the proliferation of Japanese object when she tries to escape the shoji room. When Arakau tries to grab her the first time, she retreats back to a corner in front of a wall with eerie dark paintings and curls up beside a brass buddha statue. The fake sakura flower that she played curiously with earlier is placed to her left and a wisp of smoke rises ominously from the brass brazier on Arakau’s desk. When he drags her from the wall to the table, he has to swept off a bunch of small-piece art objects off his wooden table with intricate carvings and shallow thin notches on the side to clear some space. On the right side, a dimly lighted lantern projects a glow. The costume of Araku in the scene is also worth noting. He wears parts of the classic three-piece suit ---- white short, bow-tie and vest on the inside. On the outside, he wears a kimono, a traditional Japanese costume, with fine white geometric pattern on the outside. The mixture of two kinds of costume tells his identity precisely --- a well-established Japanese man in the western world, someone who is Americanized on the surface, but could not truly assimilate with the culture due to his deep-down Japanese identity.

All of these props and costume, from sakura flower, kimino, buddha statue and lanterns are all representative symbols of Japanese culture. They are considered both “primitive” and “spiritual” in the eyes of middle-class Americans and are accepted favorably in accordance with the middle-class discourse on arts and the home from the late 1870s. (Miyao 31) Lanterns are object for illumination and lighting during pre-modern times, which is completely outdated for a modern urban life, signifying its “primitiveness”. Buddha statue and Sakura flower, on the other hand, possess a sense of spirituality or moral purity. Buddha statue is a symbol for Buddhism, a widespread belief and religion in Japan, focusing on personal spiritual development. Sakura, or cherry blossom, under Japanese culture context, is a metaphor for the the ephemeral nature of life. For the audience, the spectatorship of these objects within Arakau’s shoji room not only provides them with satisfaction of their curiosity for an unknown, mysterious and different culture but also great aesthetic pleasure and appreciation of the “primitive” and “spiritual”.

The fascination for the character Hara Arakau in The Cheat among the audience arises mainly due to four different reasons. First, the extensive usage of medium shots distances the viewers from the violence displayed by the character, providing them with a safe and comfortable space for spectatorship. Second, the lack of close up shots on the facial expressions of Arakau disconnects the character with the audience, forcing him to stay exactly like the stereotypical villain and thus relieving them of the burden to engage in deeper and more complicated racial questions. After establishing a burden-free, safe and sound viewing environment, the film provides extravagant props and costumes that not only satisfies their curiosity for an exotic culture, but also provides them with aesthetic pleasure for spectatorship. "<>"" && "

从dropbox里翻出来的大一时候写的文章,凑活着看吧,主要讲了早川雪洲(好莱坞第一位亚裔明星)在这部电影里演的那个角色Hara Arakau,本应该是一个威胁到美国白人中产家庭价值观的反派角色是如何引起观众迷恋的。(主要就是通过对反派实施重要暴力镜头的cut off 还有distancing,让观众得以在一个舒适的区间进行“欣赏”不至于“恐惧”和“反感”,并且通过服化道极尽表现人物身上异域文化的“神秘性”和“欣赏价值”)

Light shines on a Japanese man in his kimono, gradually illuminating his face, his chest and his hands, which remain crossed in front of him, distancing him a bit from the viewers. He sits at his desk slightly tilted against a completely black backdrop, stares with a serious look for a short while, turns his head and starts working with those strangely shaped but finitely carved objects on the desk. Removing the lid of a brass brazier by one hand, holding a long, stick shaped wooden object in the other, he blows slightly over the brazier, and smoke swirls ominously over his face. He then puts the object inside the brazier, lift it out, and stamps his mark onto the base of an ivory statue. A rapid cut to a close up of his mark: a few strokes that constitute a shape that resembles a temple. He seems satisfied with his work and turns off the lights, leaving us with complete darkness with only a glow coming from the brazier. He stands up a little and the glow lands on half of his face. He puts back the lid of the burner and shadow of cross stripes casts over his face, mystifying his facial expressions.

Accompanied by the beautifully written exotic score played by violin, piano and flute, this scene, the very first scene of the 1915 film The Cheat, introduces us to Hara Arakau, a mysterious, wealthy Japanese art dealer who lives among white middle-class Americans in Long Island. Upon release, The Cheat achieved big box office success. However, instead of being impressed by the leading actress Fannie Ward, the audience became more fascinated with the supporting Japanese actor, Sessue Hayakawa, who played the role of Arakau. This fascination opened a gate for him to become a “full-fledged star” and to achieve superstardom eventually. (Miyao 21) In this essay, I will try to explain this fascination with Arakau through a close analysis of film techniques such as medium shots, extremely extravagant props and costumes in the scene where Arakau assaults Edith Hardy and brutally brands his mark on her shoulder --- the culmination of Arakau as an evil outsider.

The Cheat tells the story of Arakau, the rich Japanese art dealer, offers his money to Edith Hardy, a white middle class woman who has extravagant tastes, after she lost the money from the Red Cross Fund in a failed investment. In exchange, he asks for “the cheat”. Mrs. Hardy tries to return the money after her husband’s success in stock market but gets turned down and violently assaulted by Arakau. During the fight, she shots Arakau. Knowing everything, Mr. Hardy attempts to take the charges to save her name, but Mrs. Hardy confesses the truth during the trial, Arakau gets attacked by the court audience and the couple gets reunited eventually.

First, the film utilizes almost solely medium shots to safely distance the viewers from Arakau when he demonstrates violence and avoids close up shots on his face to relieve them of the burden of getting emotionally attached. The “branding” scene which demonstrates the most physical violence in the entire film consists of mainly three shots: a medium shot of Arakau dragging Mrs. Hardy from the wall and forcing her to lay on his working desk with her faces down, a medium close up shot of Arakau brands his mark onto the the back of her shoulder despite of her fierce struggle, and a medium shot of Arakau pulls her up from the desk, shoves her heavily and she falls down to the floor. Throughout this entire sequence of shots which obviously involves intense physical conflicts and emotions, there is a strong presence of “distance” from the camera to Arakau created by the extensive usage of medium shots and a clear absence of details on the face of Arakau caused by lack of close up shots.

In the medium close up shot of when Arakau conducts the “branding”, which is an extreme form of violence as it exerts great pain, the actual “branding” is cut out of sight. The audience could not see how the scaldingly hot marking tool directly touches the skin of Mrs. Hardy’s shoulder. They could only infer that the “branding” happens through the swirling smoke that rises and the fidgeting arms of Mrs. Hardy. By leaving this extreme violence out of sight, the audience could experience the thrill of “being in danger” without having to bear the pain or feeling unsafe and unsettled. When other forms of slightly lighter violence such as pulling hair, shoving and dragging are displayed in the same scene, the film utilizes a similar strategy --- medium shot. A medium shot automatically creates distance between the object being filmed and the camera. In this case, the distance created would buffer the intensity of the violence for the audience and safely protect them from the “threat” or “danger” that Arakau signifies, leaving them a safe and comfortable space for spectatorship. In other words, when Arakau demonstrates violence on screen, he is a symbol of threat, but this threat is carefully contained in the film through either cutting it completely out of the frame or a medium shot that distance the viewers from it, creating a shield of protection. Therefore, the audience could experience the excitement and thrill one one hand, but also feel safe and comfortable on the other as the “violence” experienced by the female protagonist does not exert on themselves directly. This “thrill but safe” viewing experience provides a foundation for the fascination towards the character Arakau.

It is also worth noting that there is an absence of close up shots featuring the facial expressions of Arakau. Even in the medium-close up shot of the “branding”, he faces slightly downwards towards the desk, with shadows of Mrs. Hardy’s struggling arms keep crossing his face from time to time, making his facial expressions barely discernible to the audience. The audience could only observe his deep frowns, nasolabial folds, indicating he is putting in great effort, but no other information regarding his mental state is being disclosed or revealed. Thus, unable to observe the subtle changes of minute details on Arakau’s face in this critical scene, the audience would fail to connect with the character, to actually understand his feelings and thoughts when he displays these violent behavior, not to mention to empathize or identify with him. This disconnection with the character forces Arakau to stay at the stereotypical image of a Japanese sinister rather than being treated as a unique individual. In other words, since questions like “why does he do this”, “what does he feel when he is doing this” remain unanswered, the viewers could attribute his violent behavior of assaulting Mrs. Hardy to something “evil” or “sinful” innate within him, or worse to some “nature” of his race, culture, or ethnic group. This result might be undesirable in terms of removing racial stereotypes, but it is desirable to the audience as the film provides them with a simple reductive approach to a huge, complicated racial problem. Since Arakau is pictured nothing more than the stereotypical Japanese sinister in the film, the viewers could naturally treat him as one, relieving them of the responsibility to discuss more deeply involved racial issues. Without this agonizing psychology burden of discussing racial stereotypes, the viewers could immerse themselves more in the spectatorship of the character Hara Arakau.

Apart from strategically selecting shot types to create a safe and comfortable space for spectatorship, The Cheat tooks advantage of mise-en-scene elements such as extravagant costumes and props to highlight the mysteriousness and exoticness of Arakau as an “outsider” of white middle-class Americans in New York city. The spectatorship of racial difference itself provides great aesthetic pleasure and joy for the audience which is at the core of the fascination with Hara Arakau.

The “branding” took place inside Arakau’s shoji room rather than his modernized, western style living room that holds the Red Cross Ball, hinting his unassimilable Japanese identity. In the scene where fierce physical conflicts occurred, we could see how Mrs. Hardy is encompassed by the proliferation of Japanese object when she tries to escape the shoji room. When Arakau tries to grab her the first time, she retreats back to a corner in front of a wall with eerie dark paintings and curls up beside a brass buddha statue. The fake sakura flower that she played curiously with earlier is placed to her left and a wisp of smoke rises ominously from the brass brazier on Arakau’s desk. When he drags her from the wall to the table, he has to swept off a bunch of small-piece art objects off his wooden table with intricate carvings and shallow thin notches on the side to clear some space. On the right side, a dimly lighted lantern projects a glow. The costume of Araku in the scene is also worth noting. He wears parts of the classic three-piece suit ---- white short, bow-tie and vest on the inside. On the outside, he wears a kimono, a traditional Japanese costume, with fine white geometric pattern on the outside. The mixture of two kinds of costume tells his identity precisely --- a well-established Japanese man in the western world, someone who is Americanized on the surface, but could not truly assimilate with the culture due to his deep-down Japanese identity.

All of these props and costume, from sakura flower, kimino, buddha statue and lanterns are all representative symbols of Japanese culture. They are considered both “primitive” and “spiritual” in the eyes of middle-class Americans and are accepted favorably in accordance with the middle-class discourse on arts and the home from the late 1870s. (Miyao 31) Lanterns are object for illumination and lighting during pre-modern times, which is completely outdated for a modern urban life, signifying its “primitiveness”. Buddha statue and Sakura flower, on the other hand, possess a sense of spirituality or moral purity. Buddha statue is a symbol for Buddhism, a widespread belief and religion in Japan, focusing on personal spiritual development. Sakura, or cherry blossom, under Japanese culture context, is a metaphor for the the ephemeral nature of life. For the audience, the spectatorship of these objects within Arakau’s shoji room not only provides them with satisfaction of their curiosity for an unknown, mysterious and different culture but also great aesthetic pleasure and appreciation of the “primitive” and “spiritual”.

The fascination for the character Hara Arakau in The Cheat among the audience arises mainly due to four different reasons. First, the extensive usage of medium shots distances the viewers from the violence displayed by the character, providing them with a safe and comfortable space for spectatorship. Second, the lack of close up shots on the facial expressions of Arakau disconnects the character with the audience, forcing him to stay exactly like the stereotypical villain and thus relieving them of the burden to engage in deeper and more complicated racial questions. After establishing a burden-free, safe and sound viewing environment, the film provides extravagant props and costumes that not only satisfies their curiosity for an exotic culture, but also provides them with aesthetic pleasure for spectatorship. "<>"暂时没有网友评论该影片"}

从dropbox里翻出来的大一时候写的文章,凑活着看吧,主要讲了早川雪洲(好莱坞第一位亚裔明星)在这部电影里演的那个角色Hara Arakau,本应该是一个威胁到美国白人中产家庭价值观的反派角色是如何引起观众迷恋的。(主要就是通过对反派实施重要暴力镜头的cut off 还有distancing,让观众得以在一个舒适的区间进行“欣赏”不至于“恐惧”和“反感”,并且通过服化道极尽表现人物身上异域文化的“神秘性”和“欣赏价值”)

Light shines on a Japanese man in his kimono, gradually illuminating his face, his chest and his hands, which remain crossed in front of him, distancing him a bit from the viewers. He sits at his desk slightly tilted against a completely black backdrop, stares with a serious look for a short while, turns his head and starts working with those strangely shaped but finitely carved objects on the desk. Removing the lid of a brass brazier by one hand, holding a long, stick shaped wooden object in the other, he blows slightly over the brazier, and smoke swirls ominously over his face. He then puts the object inside the brazier, lift it out, and stamps his mark onto the base of an ivory statue. A rapid cut to a close up of his mark: a few strokes that constitute a shape that resembles a temple. He seems satisfied with his work and turns off the lights, leaving us with complete darkness with only a glow coming from the brazier. He stands up a little and the glow lands on half of his face. He puts back the lid of the burner and shadow of cross stripes casts over his face, mystifying his facial expressions.

Accompanied by the beautifully written exotic score played by violin, piano and flute, this scene, the very first scene of the 1915 film The Cheat, introduces us to Hara Arakau, a mysterious, wealthy Japanese art dealer who lives among white middle-class Americans in Long Island. Upon release, The Cheat achieved big box office success. However, instead of being impressed by the leading actress Fannie Ward, the audience became more fascinated with the supporting Japanese actor, Sessue Hayakawa, who played the role of Arakau. This fascination opened a gate for him to become a “full-fledged star” and to achieve superstardom eventually. (Miyao 21) In this essay, I will try to explain this fascination with Arakau through a close analysis of film techniques such as medium shots, extremely extravagant props and costumes in the scene where Arakau assaults Edith Hardy and brutally brands his mark on her shoulder --- the culmination of Arakau as an evil outsider.

The Cheat tells the story of Arakau, the rich Japanese art dealer, offers his money to Edith Hardy, a white middle class woman who has extravagant tastes, after she lost the money from the Red Cross Fund in a failed investment. In exchange, he asks for “the cheat”. Mrs. Hardy tries to return the money after her husband’s success in stock market but gets turned down and violently assaulted by Arakau. During the fight, she shots Arakau. Knowing everything, Mr. Hardy attempts to take the charges to save her name, but Mrs. Hardy confesses the truth during the trial, Arakau gets attacked by the court audience and the couple gets reunited eventually.

First, the film utilizes almost solely medium shots to safely distance the viewers from Arakau when he demonstrates violence and avoids close up shots on his face to relieve them of the burden of getting emotionally attached. The “branding” scene which demonstrates the most physical violence in the entire film consists of mainly three shots: a medium shot of Arakau dragging Mrs. Hardy from the wall and forcing her to lay on his working desk with her faces down, a medium close up shot of Arakau brands his mark onto the the back of her shoulder despite of her fierce struggle, and a medium shot of Arakau pulls her up from the desk, shoves her heavily and she falls down to the floor. Throughout this entire sequence of shots which obviously involves intense physical conflicts and emotions, there is a strong presence of “distance” from the camera to Arakau created by the extensive usage of medium shots and a clear absence of details on the face of Arakau caused by lack of close up shots.

In the medium close up shot of when Arakau conducts the “branding”, which is an extreme form of violence as it exerts great pain, the actual “branding” is cut out of sight. The audience could not see how the scaldingly hot marking tool directly touches the skin of Mrs. Hardy’s shoulder. They could only infer that the “branding” happens through the swirling smoke that rises and the fidgeting arms of Mrs. Hardy. By leaving this extreme violence out of sight, the audience could experience the thrill of “being in danger” without having to bear the pain or feeling unsafe and unsettled. When other forms of slightly lighter violence such as pulling hair, shoving and dragging are displayed in the same scene, the film utilizes a similar strategy --- medium shot. A medium shot automatically creates distance between the object being filmed and the camera. In this case, the distance created would buffer the intensity of the violence for the audience and safely protect them from the “threat” or “danger” that Arakau signifies, leaving them a safe and comfortable space for spectatorship. In other words, when Arakau demonstrates violence on screen, he is a symbol of threat, but this threat is carefully contained in the film through either cutting it completely out of the frame or a medium shot that distance the viewers from it, creating a shield of protection. Therefore, the audience could experience the excitement and thrill one one hand, but also feel safe and comfortable on the other as the “violence” experienced by the female protagonist does not exert on themselves directly. This “thrill but safe” viewing experience provides a foundation for the fascination towards the character Arakau.

It is also worth noting that there is an absence of close up shots featuring the facial expressions of Arakau. Even in the medium-close up shot of the “branding”, he faces slightly downwards towards the desk, with shadows of Mrs. Hardy’s struggling arms keep crossing his face from time to time, making his facial expressions barely discernible to the audience. The audience could only observe his deep frowns, nasolabial folds, indicating he is putting in great effort, but no other information regarding his mental state is being disclosed or revealed. Thus, unable to observe the subtle changes of minute details on Arakau’s face in this critical scene, the audience would fail to connect with the character, to actually understand his feelings and thoughts when he displays these violent behavior, not to mention to empathize or identify with him. This disconnection with the character forces Arakau to stay at the stereotypical image of a Japanese sinister rather than being treated as a unique individual. In other words, since questions like “why does he do this”, “what does he feel when he is doing this” remain unanswered, the viewers could attribute his violent behavior of assaulting Mrs. Hardy to something “evil” or “sinful” innate within him, or worse to some “nature” of his race, culture, or ethnic group. This result might be undesirable in terms of removing racial stereotypes, but it is desirable to the audience as the film provides them with a simple reductive approach to a huge, complicated racial problem. Since Arakau is pictured nothing more than the stereotypical Japanese sinister in the film, the viewers could naturally treat him as one, relieving them of the responsibility to discuss more deeply involved racial issues. Without this agonizing psychology burden of discussing racial stereotypes, the viewers could immerse themselves more in the spectatorship of the character Hara Arakau.

Apart from strategically selecting shot types to create a safe and comfortable space for spectatorship, The Cheat tooks advantage of mise-en-scene elements such as extravagant costumes and props to highlight the mysteriousness and exoticness of Arakau as an “outsider” of white middle-class Americans in New York city. The spectatorship of racial difference itself provides great aesthetic pleasure and joy for the audience which is at the core of the fascination with Hara Arakau.

The “branding” took place inside Arakau’s shoji room rather than his modernized, western style living room that holds the Red Cross Ball, hinting his unassimilable Japanese identity. In the scene where fierce physical conflicts occurred, we could see how Mrs. Hardy is encompassed by the proliferation of Japanese object when she tries to escape the shoji room. When Arakau tries to grab her the first time, she retreats back to a corner in front of a wall with eerie dark paintings and curls up beside a brass buddha statue. The fake sakura flower that she played curiously with earlier is placed to her left and a wisp of smoke rises ominously from the brass brazier on Arakau’s desk. When he drags her from the wall to the table, he has to swept off a bunch of small-piece art objects off his wooden table with intricate carvings and shallow thin notches on the side to clear some space. On the right side, a dimly lighted lantern projects a glow. The costume of Araku in the scene is also worth noting. He wears parts of the classic three-piece suit ---- white short, bow-tie and vest on the inside. On the outside, he wears a kimono, a traditional Japanese costume, with fine white geometric pattern on the outside. The mixture of two kinds of costume tells his identity precisely --- a well-established Japanese man in the western world, someone who is Americanized on the surface, but could not truly assimilate with the culture due to his deep-down Japanese identity.

All of these props and costume, from sakura flower, kimino, buddha statue and lanterns are all representative symbols of Japanese culture. They are considered both “primitive” and “spiritual” in the eyes of middle-class Americans and are accepted favorably in accordance with the middle-class discourse on arts and the home from the late 1870s. (Miyao 31) Lanterns are object for illumination and lighting during pre-modern times, which is completely outdated for a modern urban life, signifying its “primitiveness”. Buddha statue and Sakura flower, on the other hand, possess a sense of spirituality or moral purity. Buddha statue is a symbol for Buddhism, a widespread belief and religion in Japan, focusing on personal spiritual development. Sakura, or cherry blossom, under Japanese culture context, is a metaphor for the the ephemeral nature of life. For the audience, the spectatorship of these objects within Arakau’s shoji room not only provides them with satisfaction of their curiosity for an unknown, mysterious and different culture but also great aesthetic pleasure and appreciation of the “primitive” and “spiritual”.

The fascination for the character Hara Arakau in The Cheat among the audience arises mainly due to four different reasons. First, the extensive usage of medium shots distances the viewers from the violence displayed by the character, providing them with a safe and comfortable space for spectatorship. Second, the lack of close up shots on the facial expressions of Arakau disconnects the character with the audience, forcing him to stay exactly like the stereotypical villain and thus relieving them of the burden to engage in deeper and more complicated racial questions. After establishing a burden-free, safe and sound viewing environment, the film provides extravagant props and costumes that not only satisfies their curiosity for an exotic culture, but also provides them with aesthetic pleasure for spectatorship.